|

|

10 January 1918 - German Fokker D.VII

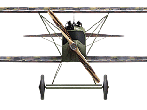

The Fokker D.VII is widely regarded as the best German aircraft of the war. Its development was championed by Manfred von Richthofen. In January 1918, Richthofen tested the D.VII in the trials at Adlershof but never had an opportunity to fly it in combat. He was killed just days before it entered service. When introduced, the D.VII was not without problems. On occasion its wing ribs would fracture in a dive and high temperatures sometimes ignited planes armed with phosphorus ammunition or caused their gas tanks to explode. Even so, the D.VII proved to be durable and easy to fly. As noted by one authority, it had "an apparant ability to to make a good pilot out of mediocre material." When equipped with the BMW engine, the D.VII could outclimb any Allied opponent it encountered in combat. Highly maneuverable at all speeds and altitudes, it proved to be more than a match for any of the British or French fighter planes of 1918. Hermann Göring was one of the first pilots to fly the D.VII in combat.

The Fokker D.VII was a German World War I fighter aircraft designed by Reinhold Platz of the Fokker-Flugzeugwerke. Germany produced around 3,300 D.VII aircraft in the summer and autumn of 1918. In service, the D.VII quickly proved itself to be a formidable aircraft. The Armistice ending the war specifically required Germany to surrender all D.VIIs to the Allies at the conclusion of hostilities. Surviving aircraft saw continued widespread service with many other countries in the years after World War I.

Development and production

Fokker's chief designer, Reinhold Platz, had been working on a series of experimental planes, the V-series, since 1916. These planes were characterized by the use of cantilever wings, first developed during Fokker's government-mandated collaboration with Hugo Junkers. Junkers had originated the idea in 1915 with the first all-metal aircraft, the Junkers J 1, nicknamed Blechesel ("Sheet Metal Donkey" or "Tin Donkey"). The resulting wings were thick, with a rounded leading edge. This gave greater lift and more docile stalling behavior than conventional thin wings.

Late in 1917, Fokker built the experimental V 11 biplane, fitted with the standard Mercedes D.IIIa engine. In January 1918, Idflieg held a fighter competition at Adlershof. For the first time, frontline pilots would directly participate in the evaluation and selection of new fighters. Fokker submitted the V 11 along with several other prototypes. Manfred von Richthofen flew the V 11 and found it tricky, unpleasant, and directionally unstable in a dive. In response to these complaints, Reinhold Platz lengthened the rear fuselage by one structural bay, and added a triangular fixed vertical fin in front of the rudder. Upon flying the modified V 11, Richthofen praised it as the best aircraft of the competition. It offered excellent performance from the outdated Mercedes engine, yet it was safe and easy to fly. Richthofen's recommendation virtually decided the competition, but he was not alone in recommending it. Fokker immediately received a provisional order for 400 production aircraft, which were designated D.VII by Idflieg.

Fokker's factory was not up to the task of meeting all D.VII production orders. Idflieg therefore directed Albatros and AEG to build the D.VII under license, though AEG did not ultimately produce any aircraft. Because the Fokker factory did not use detailed plans as part of its production process, Fokker simply sent a completed D.VII airframe for Albatros to copy. Albatros paid Fokker a five percent royalty for every D.VII built under license. Albatros Flugzeugwerke and its subsidiary, Ostdeutsche Albatros Werke (OAW), built the D.VII at factories in Johannisthal (designated Fokker D.VII (Alb)) and Schneidemühl (Fokker D.VII (OAW)), respectively. Aircraft markings included the type designation and factory suffix, immediately before the individual serial number.

Some parts were not interchangeable between aircraft produced at different factories, even between Albatros and OAW.Additionally each manufacturer tended to differ in nose paint styles. OAW produced examples were delivered with distinctive mauve and green splotches on the cowling. All D.VIIs were produced with the lozenge camouflage covering except for early Fokker-produced D.VIIs, which had a streaked green fuselage. Factory camouflage finishes were often overpainted with colorful paint schemes or insignia for the Jasta, or the individual pilot.

Albatros soon surpassed Fokker in the quantity and workmanship quality of aircraft produced With a massive production program, over 3,000 to 3,300 D.VII aircraft were delivered from all three plants, considerably more than the commonly quoted but incorrect production figure of 1,700

In September 1918, eight D.VIIs were delivered to Bulgaria. Late in 1918, the Austro-Hungarian company MÁG (Magyar Általános Gépgyár - Hungarian General Machine Company) commenced licensed production of the D.VII with Austro-Daimler engines. Production continued after the end of the war, with as many as 50 aircraft completed.

Powerplants

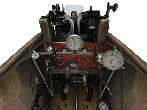

Many sources erroneously state that the D.VII was equipped with the 120 kW (160 hp) Mercedes D.III engine. The Germans themselves used the generic D.III designation to describe later versions of that engine. In fact, the earliest production D.VIIs were equipped with 170-180 hp Mercedes D.IIIa. Production quickly switched to the intended standard engine, the higher-compression 134 kW (180-200 hp) Mercedes D.IIIa. It appears that some early production D.VIIs delivered with the Mercedes D.IIIa were later re-engined with the D.IIIa

By the summer of 1918, a number of D.VIIs received the "overcompressed" 138 kW (185 hp) BMW IIIa, the first product of the BMW firm. The BMW IIIa followed the SOHC, straight-six configuration of the Mercedes D.III, but incorporated several improvements. Increased displacement, higher compression, and an altitude-adjusting carburetor produced a marked increase in speed and climb rate at high altitude. Because the BMW IIIa was overcompressed, using full throttle at altitudes below 2,000 m (6,700 ft) risked premature detonation in the cylinders and damage to the engine. At low altitudes, full throttle could produce up to 179 kW (240 hp) for a short time. Fokker-built aircraft with the new BMW engine were designated D.VII(F), the suffix "F" standing for Max Friz, the engine's designer. Some Albatros-built aircraft may also have received a separate designation.

BMW-engined aircraft entered service with Jasta 11 in late June 1918. Pilots clamored for the D.VII(F), of which about 750 were built. However, production of the BMW IIIa was very limited and the D.VII continued to be produced with the 134 kW (180 hp) Mercedes D.IIIa until the end of the war.

D.VIIs flew with different propeller designs from different manufacturers. Despite the differing appearances there is no indication these propellers gave disparate performance. Axial, Wolff, Wotan, and Heine propellers have been noted.

Operational history

The D.VII entered squadron service with Jasta 10 in early May 1918. The type quickly proved to have many important advantages over the Albatros and Pfalz scouts. Unlike the Albatros scouts, the D.VII could dive without any fear of structural failure. The D.VII was also noted for its high maneuverability and ability to climb at high angles of attack, its remarkably docile stall, and its reluctance to spin. It could literally "hang on its prop" without stalling for brief periods of time, spraying enemy aircraft from below with machine gun fire. These handling characteristics contrasted with contemporary scouts such as the Camel and SPAD, which stalled sharply and spun vigorously.

However, the D.VII also had problems. Several aircraft suffered rib failures and fabric shedding on the upper wing. Heat from the engine sometimes ignited phosphorus ammunition until cooling vents were installed in the engine cowling, and fuel tanks sometimes broke at the seams. Aircraft built by the Fokker factory at Schwerin were noted for their lower standard of workmanship and materials. Nevertheless, the D.VII proved to be a remarkably successful design, leading to the familiar aphorism that it could turn a mediocre pilot into a good one, and a good pilot into an ace.

Manfred von Richthofen died only days before the D.VII began to reach the Jagdstaffeln and never flew it in combat. Other pilots, including Erich Löwenhardt and Hermann Göring, quickly racked up victories and generally lauded the design. Aircraft availability was limited at first, but by July there were 407 on charge. Larger numbers became available by August, when D.VIIs achieved 565 victories. The D.VII eventually equipped 46 Jagdstaffeln. When the war ended in November, 775 D.VII aircraft were in service.

German Fokker D.VII SPECIFICATIONS

Country: Germany

Manufacturer: Fokker Flugzeug-Werke GmbH

Albatros-Werke Johannisthal

Ostdeutsche Albatros-Werke Schneidemuhl (OAW)

Type: Fighter

First Service: Late March or early April 1918

Number Built: About 2,694

Engine(s): Mercedes D-III 6 cylinder liquid cooled inline, 160 hp

BMW IIIa inline, 185 hp

Wing Span: 29 ft 3.5 in

Length: 22 ft 11.5 in

Height: 9 ft 2.5 in

Empty Weight: 1,540 lb

Gross Weight: 1,939 lb

Max Speed: 118 mph (Mercedes)

124 mph (BMW)

Ceiling: 18,000 ft (Mercedes)

21,000 ft (BMW)

Endurance: 1.5 hours

Crew: 1

Armament: 2 Spandau 7.92 mm machine guns

The Fokker D.VII was a German World War I fighter aircraft produced at around 3,300 aircraft between summer and autumn of 1918. In service, the D.VII quickly proved itself to be a formidable aircraft. The Armistice ending the war specifically required Germany to surrender all D.VIIs to the Allies at the conclusion of hostilities. Surviving aircraft saw continued widespread service with many other countries in the years after World War I.

|